Key Takeaways:

- The global hydrogen economy in the power sector is shifting hydrogen from a niche industrial gas into a widely traded, low‑carbon energy commodity, with governments, utilities, and investors aligning policy, infrastructure and technology around green and blue hydrogen to decarbonise electricity generation, provide long‑duration storage, and unlock new cross‑border energy trade patterns over the next two decades.

- Utilities and power producers are positioning hydrogen for power generation, storage and grid balancing by piloting hydrogen-ready gas turbines, co-firing in existing thermal plants, and developing large-scale storage in salt caverns and depleted gas fields, while grappling with challenges around supply-demand synchronisation, costs, certifications, and the build-out of pipelines, terminals and regional hydrogen hubs.

The global hydrogen economy in the power sector is no longer an abstract vision discussed only in policy papers and conference panels. It is taking a discernible shape on the ground, as projects, regulations, trade routes and long‑term contracts begin to resemble a structured energy commodity market rather than a collection of pilot schemes. For utilities and power producers, hydrogen is emerging as a versatile tool: a decarbonised fuel for thermal power generation, a long‑duration storage medium for variable renewables, and a flexible asset for grid balancing in an increasingly electrified world.

Understanding how this global hydrogen economy in the power sector is forming requires looking at three intertwined dimensions: supply–demand dynamics, emerging hydrogen trade routes, and strategic responses from utilities and power producers.

Global supply demand dynamics for hydrogen in power

Early hydrogen demand was concentrated in industrial uses such as refining, fertilisers and chemicals, supplied predominantly by hydrogen produced from natural gas without carbon capture. As climate policy has tightened, attention has shifted towards low‑carbon hydrogen, especially green hydrogen made via electrolysis using renewable electricity and blue hydrogen produced from natural gas with carbon capture and storage.

In the near term, demand from the power sector competes with industrial decarbonisation for limited volumes of low‑carbon hydrogen. Refiners, steelmakers and chemical producers often have clearer existing hydrogen uses and can absorb early volumes even at premium prices. However, the power sector offers a uniquely scalable outlet. Gas turbines, combined‑cycle plants and dedicated hydrogen power plants can in principle consume very large quantities of hydrogen once supply is available and costs fall.

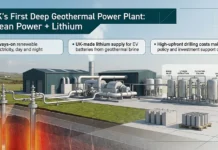

On the supply side, resource‑rich regions with excellent solar and wind potential are positioning themselves as exporters in the global hydrogen economy. Countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Australia and parts of Latin America are designing giga‑scale renewable projects dedicated to green hydrogen production, aiming to ship hydrogen as ammonia, liquid hydrogen or other derivatives. At the same time, regions with abundant natural gas reserves and storage potential are developing blue hydrogen at scale, using carbon capture to lower emissions intensity.

For power-sector planners, the key challenge is matching this evolving supply landscape with credible, bankable demand in electricity generation. Long‑term offtake agreements, capacity mechanisms that reward low‑carbon flexibility, and clear standards for what counts as “green” or “low‑carbon” hydrogen will determine whether hydrogen-fired power plants are built in significant numbers.

Emerging hydrogen trade routes and infrastructure

As the global hydrogen economy in the power sector matures, infrastructure decisions being made today will lock in trade patterns for decades. Unlike electrons on a wire, hydrogen requires dedicated physical systems: production facilities, pipelines, storage sites, export terminals and import handling infrastructure.

Several potential trade routes are crystallising. One category links high‑renewable-resource exporters to demand centres with limited domestic resources, such as hydrogen shipments from Australian solar and wind hubs to power‑hungry markets in East Asia. Another connects North African or Middle Eastern exporters to European grids seeking to decarbonise both industry and power generation. There is also a prospective intra‑regional trade within large markets like North America, where hydrogen may move from resource‑rich interior regions to coastal load centres via repurposed or new pipelines.

For the power sector, the form in which hydrogen is traded matters. Shipping hydrogen as ammonia can leverage existing ammonia infrastructure and enable direct use in some industrial processes, but reconversion to hydrogen for power generation involves energy losses and added cost. Liquid hydrogen transport demands cryogenic technology and specialised ships. Synthetic fuels derived from hydrogen, such as methanol or e‑kerosene, might serve niche generation applications but add further conversion steps.

Utilities assessing future import dependency must weigh these trade-offs against domestic production options. Some countries favour a “hydrogen backbone” approach, building or repurposing transmission‑scale pipelines to move hydrogen from coastal import terminals or onshore production hubs to inland power plants. Others anticipate more decentralised production integrated with renewable assets close to demand centres, reducing long‑distance transport needs.

Hydrogen’s role in power generation and grid balancing

Within the power sector, hydrogen’s value proposition spans three main functions: fuel for dispatchable generation, medium for long‑duration energy storage, and asset for ancillary services and grid balancing.

As a fuel, hydrogen can be combusted in modified gas turbines or engines, used in combined‑cycle configurations, or even utilised in high‑temperature fuel cells. Many turbine manufacturers now offer hydrogen‑ready models capable of co‑firing hydrogen with natural gas, with roadmaps toward 100 percent hydrogen fuel. This pathway allows existing thermal fleets to gradually decarbonise, blending in hydrogen as it becomes available without abandoning valuable infrastructure.

Hydrogen also enables long‑duration storage that goes beyond the hours‑scale capabilities of batteries. Excess renewable electricity can be converted into hydrogen via electrolysis when prices are low or negative, stored for days, weeks or seasons, and later reconverted into electricity during periods of low renewable output or high demand. For grids targeting very high shares of wind and solar, this power‑to‑hydrogen‑to‑power cycle offers a way to maintain reliability without relying heavily on unabated fossil fuels.

Moreover, hydrogen assets can contribute to grid balancing and system services. Electrolysers can act as flexible demand, quickly ramping up consumption to absorb surplus renewable generation or ramping down to alleviate grid stress. Hydrogen‑fired plants can provide frequency response, reserve capacity and black‑start capabilities, supporting overall system stability. The global hydrogen economy in the power sector therefore extends beyond simple fuel substitution and into the architecture of a flexible, resilient electricity system.

Strategic positioning of utilities and power producers

As the contours of the global hydrogen economy become clearer, utilities and power producers are rethinking portfolios, asset strategies and partnerships. Some vertically integrated utilities are investing across the value chain, from renewable generation and electrolysis to storage and hydrogen‑ready generation assets. Others are taking a more selective approach, focusing on offtake agreements and hydrogen‑capable plants while relying on third parties for production and logistics.

A recurring strategic question is whether to prioritise green hydrogen from renewables or blue hydrogen with carbon capture. Green hydrogen aligns strongly with long‑term net‑zero visions and avoids exposure to carbon prices on residual emissions, but it depends on massive build‑out of low-cost renewables and continued improvements in electrolysis technology. Blue hydrogen can scale more rapidly where gas and storage are available, potentially offering transitional volumes for power generation while green capacity ramps up.

Regulation and market design are critical framing conditions. Capacity markets, contracts for difference, guarantees of origin and emissions standards all influence the risk–reward profile of hydrogen investments in the power sector. Utilities seeking to integrate hydrogen into long-term generation plans must navigate policy uncertainty, evolving technical standards and shifting cost curves. At the same time, early movers in the global hydrogen economy in the power sector may gain access to strategic assets, customer relationships and learning benefits that are difficult to replicate later.

Challenges, risks and pathways forward

Despite its promise, the global hydrogen economy faces substantial challenges. Production costs for green and blue hydrogen remain above those of conventional fuels on an energy-equivalent basis, even before considering conversion and transport losses. Building out dedicated infrastructure pipelines, storage, terminals requires high upfront capital and clear regulatory frameworks. Safety considerations around hydrogen handling, especially in densely populated regions, must be addressed through standards and public engagement.

There is also a risk of fragmentation. Multiple colour labels, varying carbon-intensity thresholds, and inconsistent certification systems could complicate cross-border trade and undermine investor confidence. Aligning standards so that a unit of low‑carbon hydrogen is recognised consistently across markets is an essential enabler of the global hydrogen economy in the power sector.

Yet the direction of travel is evident. As renewable costs continue to fall, electrolyser technologies improve, and international cooperation on standards and trade frameworks deepens, hydrogen is likely to become a central pillar of a decarbonised power system. For utilities and power producers, the question is less whether hydrogen will play a role and more how to position portfolios and infrastructure to benefit from its emergence as a global energy commodity.