Energy transitions succeed when physics and economics cooperate. Clean electricity from wind and solar is growing rapidly, yet the modern energy system still struggles with two practical issues: storing energy at scale and delivering clean energy in forms that industry can use for heat, mobility, and chemical production. Electrochemical technologies are at the centre of this challenge. They provide the mechanisms to convert electricity into molecules, to store energy in compact forms, and to deliver power with lower emissions. In a very real sense, electrochemistry is the bridge between electrons and molecules between renewable generation and the diverse energy demands of economies.

The key phrase electrochemical technologies clean energy systems captures this bridging role. It includes hydrogen production through electrolysis, energy storage through batteries and other electrochemical devices, and power conversion through fuel cells. While each technology has its own maturity curve and constraints, together they form a toolkit that can stabilise grids, decarbonise industrial processes, and enable more resilient energy infrastructure.

Why Electrochemistry Matters More Than Ever

Traditional power systems were built around controllable generation: coal plants, gas turbines, large hydro. Renewable power changes that logic by making generation more variable. The system therefore needs flexibility ways to shift energy through time, move it across space, and deliver it in different forms.

Electrochemical technologies are uniquely suited to flexibility because they respond quickly, can be modular, and can be scaled from small devices to grid-level installations. They also integrate naturally with digital control systems, enabling smarter dispatch and optimisation.

In the clean energy transition, the value of electrochemistry is not only in efficiency. It is also in system design: creating a portfolio of options that reduces dependency on any single infrastructure constraint.

Hydrogen Production: Electrolysis as a Clean Pathway

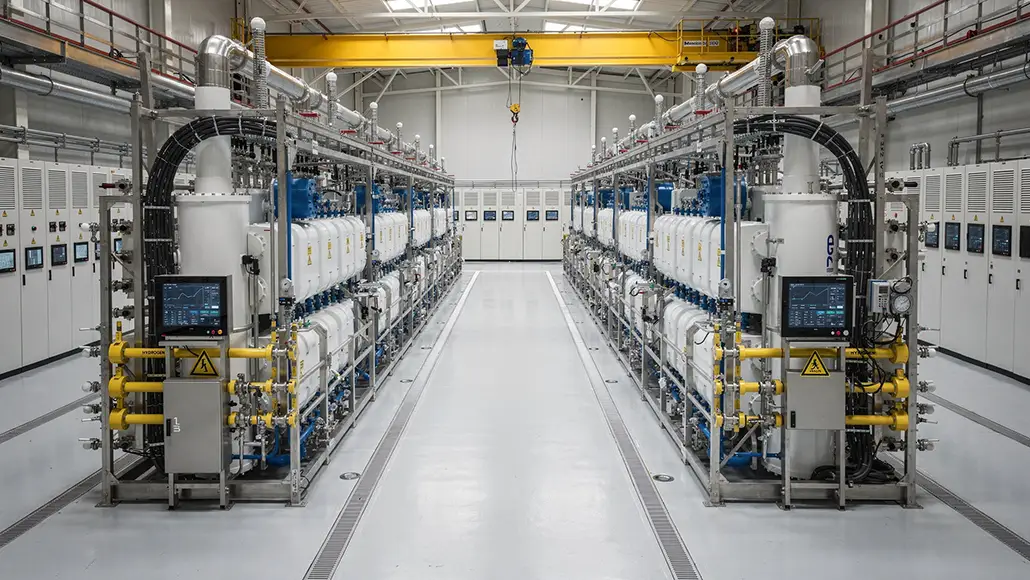

Hydrogen production via water electrolysis is often the headline application. Electrolysers use electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. When powered by low-carbon electricity, the resulting hydrogen can be a low-emission energy carrier and industrial feedstock.

Main Electrolyser Types

Alkaline electrolysers are a mature technology, often valued for durability and cost. Proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysers offer faster response and compact design, making them suitable for variable renewable inputs. Solid oxide electrolysers operate at high temperatures and can potentially achieve high efficiency, particularly when integrated with industrial waste heat, though they are less mature and face materials challenges.

Each pathway has trade-offs in capital cost, operational flexibility, water purity requirements, and maintenance. For clean energy systems, the “best” electrolyser is usually the one that matches local conditions: power price patterns, renewable variability, and the intended use of hydrogen.

The Importance of Utilisation and Power Contracts

Hydrogen cost is heavily influenced by electrolyser utilisation. Running equipment at low capacity factors can make hydrogen expensive even if the electricity price is low at certain hours. Many successful projects therefore pair electrolysis with a mix of renewable contracts, grid power, and storage to maintain high utilisation while keeping emissions low.

For industrial users, integration matters. An electrolyser supplying hydrogen to a chemical plant must deliver consistent quality and pressure. That requires compression, purification where needed, and buffer storage. The electrochemical stack is only one part of the system.

Energy Storage: Batteries as Grid and Industrial Infrastructure

If electrolysis converts electricity into molecules, batteries store electricity directly. Battery storage has become a foundational component of clean energy systems, helping manage renewable variability, provide frequency regulation, and reduce peak demand.

Lithium-ion batteries dominate today’s market due to high energy density and declining costs, but the landscape is broader. Flow batteries offer long-duration storage potential and can be scaled by enlarging electrolyte tanks. Sodium-ion batteries are emerging as a possible lower-cost alternative in certain applications. Advanced chemistries continue to evolve, aiming for better safety, longer life, and reduced reliance on constrained minerals.

For industrial facilities, batteries can provide resilience and economic value by shaving peaks, supporting critical loads, and enabling more on-site renewable utilisation. They also support electrification by reducing the impact of demand spikes on grid connections.

Fuel Cells: Converting Hydrogen Back Into Power

Fuel cells are electrochemical devices that convert hydrogen (or other fuels in some designs) into electricity and heat with high efficiency and low local emissions. They are often discussed in mobility, but they also have a role in stationary power.

In industrial settings, fuel cells can support reliable power for critical operations or provide combined heat and power where both electricity and heat are valuable. Solid oxide fuel cells, for example, can achieve high efficiency and can be integrated with industrial heat systems. Proton exchange membrane fuel cells are valued for fast response and are commonly considered for backup power and modular deployments.

Economics depend on hydrogen availability and cost, but the operational advantages quiet operation, modularity, high efficiency make fuel cells increasingly relevant for sites facing strict air quality constraints or requiring high reliability.

Power Technology Innovation Beyond the Headliners

Electrochemical technologies also include less visible but important innovations: electrochemical CO₂ conversion, electrochemical ammonia synthesis pathways under development, and electrochemical separation methods. Some of these remain early-stage, but they point toward a future where electricity directly drives chemical manufacturing with lower emissions.

Electrochemical CO₂ conversion, for example, aims to transform captured CO₂ into useful chemicals or fuels. The promise is attractive, yet the practical hurdles are significant: catalyst durability, energy efficiency, product separation, and scale. Even so, the direction is clear electrochemistry is expanding from energy storage and hydrogen production into broader industrial decarbonisation.

Materials, Supply Chains, and Scalability

A recurring challenge is materials. Electrochemical devices rely on catalysts, membranes, electrodes, and electrolytes. Some designs use scarce materials such as platinum group metals. Others use more abundant materials but require precise manufacturing.

Scaling clean energy systems therefore depends not only on technical performance, but on supply chain resilience and manufacturability. The most scalable technologies tend to be those that reduce critical material intensity, standardise components, and support high-volume production.

Industrial users should consider supply chain factors early when selecting technologies, particularly for assets expected to run for decades.

Integration Into Real Systems: The “Whole Plant” Perspective

Electrochemical technologies are most powerful when integrated thoughtfully. A renewable-powered industrial cluster might use batteries for short-term balancing, electrolysers to convert surplus electricity into hydrogen, and fuel cells or turbines to provide firm power during low renewable periods. Waste heat from industrial processes might support high-temperature electrolysis, improving overall efficiency. Digital controls might optimise the entire system based on electricity prices, grid carbon intensity, and production schedules.

This is the systems view that makes electrochemical technologies clean energy systems more than a collection of devices. It becomes an engineered ecosystem.

Safety, Standards, and Operational Readiness

Electrochemical systems are often perceived as clean and quiet, yet they bring operational risks that must be managed. Batteries require thermal management and fire safety planning. Hydrogen systems require leak detection, ventilation, and careful procedures. Fuel cells require fuel quality control and robust maintenance plans.

Standards and permitting frameworks are improving, but industrial adoption still depends on operator confidence. Projects succeed when training, maintenance planning, and safety reviews are treated as core deliverables, not afterthoughts.

Where the Next Decade Is Heading

The next wave of progress will likely be defined by cost reductions, better durability, and smarter integration. Electrolysers will improve in efficiency and manufacturing scale. Batteries will diversify into multiple chemistries, reducing reliance on constrained materials and expanding long-duration options. Fuel cells will find clearer niches where their advantages justify cost.

For policymakers and industrial leaders, the implication is straightforward: invest not only in headline projects, but also in the enabling ecosystem supply chains, workforce skills, standards, and infrastructure.

Electrochemical technologies clean energy systems are not a distant promise; they are already reshaping how energy is produced, stored, and used. As the world pushes for deeper decarbonisation, electrochemistry will increasingly determine whether clean energy remains variable and limited, or becomes firm, flexible, and industrially practical.

Word Count: TBD