In fewer than 20 years, the UK may employ up to 67,000 people in the floating offshore wind (FOW) industry, according to a recent forecast. The study uses a high, base, and low case prediction to determine that by 2040, the active workforce will need between 22,000 and 67,000 people, depending on the deployment plan the UK chooses.

It estimates that by 2040, a low-case deployment scenario with more than 18 gigawatts (GW) of floating offshore wind will necessitate a workforce of more than 31,000 active workers.

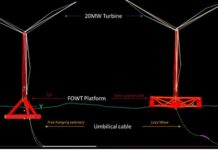

The project Floating Offshore Wind People, Skills, and Vocations describes the employment and skills required to build, run, and maintain a FOW wind farm. The workforce might total up to 67,000 people in the best-case scenario, depending on the UK’s deployment strategy.

Planning and permitting, project planning, electrical and high-voltage electrical systems, numerous occupations connected with fabrication and sophisticated manufacturing, and digital skills across all disciplines are claimed to be areas with skill shortages.

The paper emphasises the need to reduce obstacles to the transfer of military and oil and gas industry capabilities to floating offshore wind farms, particularly for marine functionality and maintenance procedures. The researchers suggest building specialised training facilities close to ports and manufacturing areas.

Another recent study from Aberdeen’s Robert Gordon University (RGU) asserts that new low-carbon technologies might create 26,000 new energy jobs in the UK by 2030. Most would reside in coastal areas along the east and west coasts of the UK. The Energy Transition Institute at RGU examined the advantages of carbon transportation and long-term subsurface collection of captured CO2 emissions, as well as electrification of offshore platforms to cut down on emissions from oil and gas. Hydrogen is a green fuel that can replace natural gas and diesel.

As part of the North Sea Transition Deal between both the UK offshore oil and gas industry as well as the UK government last year, Offshore Energies UK funded the research. The agreement recognises the industry’s contribution to ensuring reliable oil and gas supplies while also delivering low-carbon energy output, including offshore wind.

RGU evaluated three investment possibilities to determine the potential employment impact of the deal by 2030. The UK would be storing 30 MM metric tonnes of CO2 underground each year, producing 10 GW of hydrogen, which is equivalent to 10 large power plants, running 10 offshore oil or gas channels on low-carbon electricity, and hiring up to 26,000 more people, or roughly 15% of the offshore industry’s working population, if the government’s British Energy Security Strategy objectives were met by then.

Activities outside the purview of offshore businesses, such as CO2 capture, CO2 imports, facility construction, and exporting of UK technology and experience, would probably result in the creation of more jobs.

The government’s new Energy Profits Levy, which diverts 65% of the revenue from offshore oil and gas exploitation to the Treasury, has forced OEUK’s affiliates to adjust. The charge, according to OEUK’s warning, could cost the sector at least £5 billion in 2022 alone and could discourage investments in new technology.

The technology most impacted by the new charge, according to Director of Supply Chain & Operations, Katy Heidenreich, at OEUK, is electrification, but all three depend on investments made by foreign companies in UK energy.

The possibility of utilising the oil and gas industry’s knowledge to develop cleaner energy that will assist in achieving their climate targets is presented by the North Sea Transition Deal, according to the spokesperson. The UK offshore energy industry requires an environment that promotes investments and recognises the ongoing necessity of oil and gas as novel lower carbon projects and technologies come online in order to reach the greatest potential outcome stated in the report.

Furthermore, it added that long-term thinking and a predictable, stable political and investment environment are more important than ever.