Some European countries are rethinking the use of coal, one of the dirtiest and most polluting energy sources, due to reduced Russian gas flows and the threat of a complete supply disruption. Though authorities maintain that burning coal is an essential fix to help avoid a winter supply shortage, it has stoked concerns that the energy crisis could cause Europe to prolong its shift away from fossil fuels.

In terms of emissions, coal is the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel, making it the most crucial fuel to replace as a switch is made to alternate energy sources. However, coal-fired facilities may be utilised to make up for a reduction in Russian gas supplies, according to Germany, Italy, Austria, and the Netherlands.

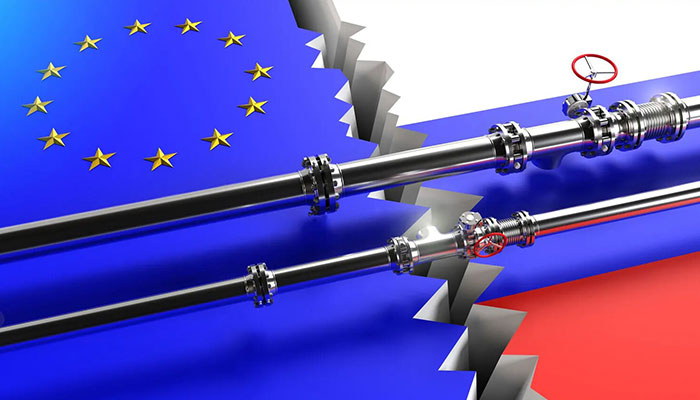

Using the delayed return of equipment maintained by Germany’s Siemens Energy in Canada as justification, Russia’s state-backed energy behemoth Gazprom has substantially reduced its use via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline, which travels to Germany beneath the Baltic Sea. It is unclear when or if the Nord Stream 1 gas flows will resume at their regular rates.

The government’s decision to restrict the use of natural gas and increase the burning of coal has been dubbed “bitter” by Robert Habeck, the German Economy Minister, but he has insisted that the nation must do all it can to stockpile as much gas as it can before the winter. During the winter, the gas storage facilities must be filled. According to a translation of a statement made by Habeck, that is of the utmost importance. It has already been made clear by Berlin that it will culminate power generation through coal by 2038 end.

According to Reuters, the Netherlands announced the week starting June 20th that it would eliminate an output cap at coal-fired facilities in an attempt to uphold gas and activate an early warning stage of an energy crisis plan. In order to counter a dramatic decline in Russian gas supplies, Italy and Austria have also indicated plans to consider burning more coal.

The short-term solution for Germany and many other European nations, according to Henning Gloystein, director of energy, environment, and resources at political risk consultancy Eurasia Group, is to use any non-Russian energy source they can, and unfortunately that does include coal.

Gloystein said that Germany has a considerable amount of lignite, the dirtiest type of coal, and that the country will likely want to optimise that supply to prevent a winter gas crisis. According to Gloystein, European authorities should be able to prevent energy rationing throughout the winter. But if Russian gas ceases flowing when it’s exceptionally cold, he cautioned, things may turn pretty unpleasant.

Energy rationing is the worst-case situation. That would include offering compensation in exchange for non-essential industries’ first reductions in consumption. Gloystein claims that this plan was disclosed by the German government over the weekend. The next stage would be to ration goods and services and ask people to consume far less, which is something that most people in Europe have never had to do, he continued. This is politically very poisonous and obviously a bad condition to be in because it implies that over the winter, people will feel cold and, in some locations, if it is a cold winter, some people will succumb.

In order to provide households with adequate fuel to keep the lights on and homes warm over the winter, European governments are currently rushing to fill root cellars with natural gas supplies. It is a part of a larger initiative by the bloc to rapidly decrease its dependency on Russian hydrocarbons in reaction to the Kremlin’s nearly four-month-long assault in Ukraine. The EU now obtains about 40% of its gas from Russian pipelines.

Dmitry Peskov, a spokesman for the Kremlin, stated that Russia had gas ready to send to Europe, but that its equipment needed to be returned first. He referred to the present conflict as a man-made problem caused by Europe. Russian supply restraints have previously been characterised by Germany’s Habeck as a political choice meant to destabilise the area and raise fuel prices.

It’s critical to comprehend the timelines behind Europe’s choice to switch to coal, according to Lauri Myllyvirta, of the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air. According to Myllyvirta, Europe was caught off guard by the situation and many steps will be necessary to get through the upcoming winter without Russian gas.

At the same time, the EU and many EU nations have recognised the problem by accelerating the installation of clean energy, meaning that they will cut the production of fossil fuels over the next few years considerably more quickly than was anticipated before the crisis. Myllyvirta continued by saying that there is room for the EU to do more in the short term to reduce the demand for fossil fuels, especially in buildings and transportation. However, it’s critical to remember that the crisis has already substantially hastened the shift to renewable energy.

In the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine, the EU has stated that it intends to speed up plans to expand production of renewable energy, such as wind and solar, while also seeking opportunities to diversify its gas supply. According to Mahi Sideridou, general director at Europe Beyond Coal, decades of unsuccessful energy and infrastructure policies have brought governments to a place where they are (re)considering coal, a resource that is responsible for a number of lives as well as irrevocable climate damage.

She said that they must now make sure that any new steps are just transitory and that they are moving toward a completely coal-free Europe by 2030. Large investments in renewable energy, including wind and solar, energy storage technologies, improved efficiency, and more, according to Sideridou, are required. This is the only way, she continued, that one can address the expense of living and climate issues and contribute to world peace.